Drones: Finding Injured Individuals in Major Disasters

Measuring a person‘s heartbeat and respiratory rate via radar is nothing new. However, researchers have now succeeded in capturing vital parameters using radar from a moving drone. This is particularly interesting for major disaster events such as earthquakes or fires.

When a building collapses during an earthquake, it is often too dangerous for rescue teams to enter and search for injured individuals. Therefore, systems that support rescue teams in exploring damage sites are urgently needed. Drone-based systems are particularly suitable: Equipped with radar sensors, drones could fly into buildings and locate injured individuals. Corresponding drone-based sensor technology has been developed by a German-Austrian consortium in the BMBF project »UAV-Rescue,« led by Fraunhofer FHR. Participants Federal Agency for Technical Relief (THW), Leibniz University Hannover (LUH), Fraunhofer EMI, and Ruhr University Bochum.

Measuring Vital Parameters via Radar on a Moving Drone

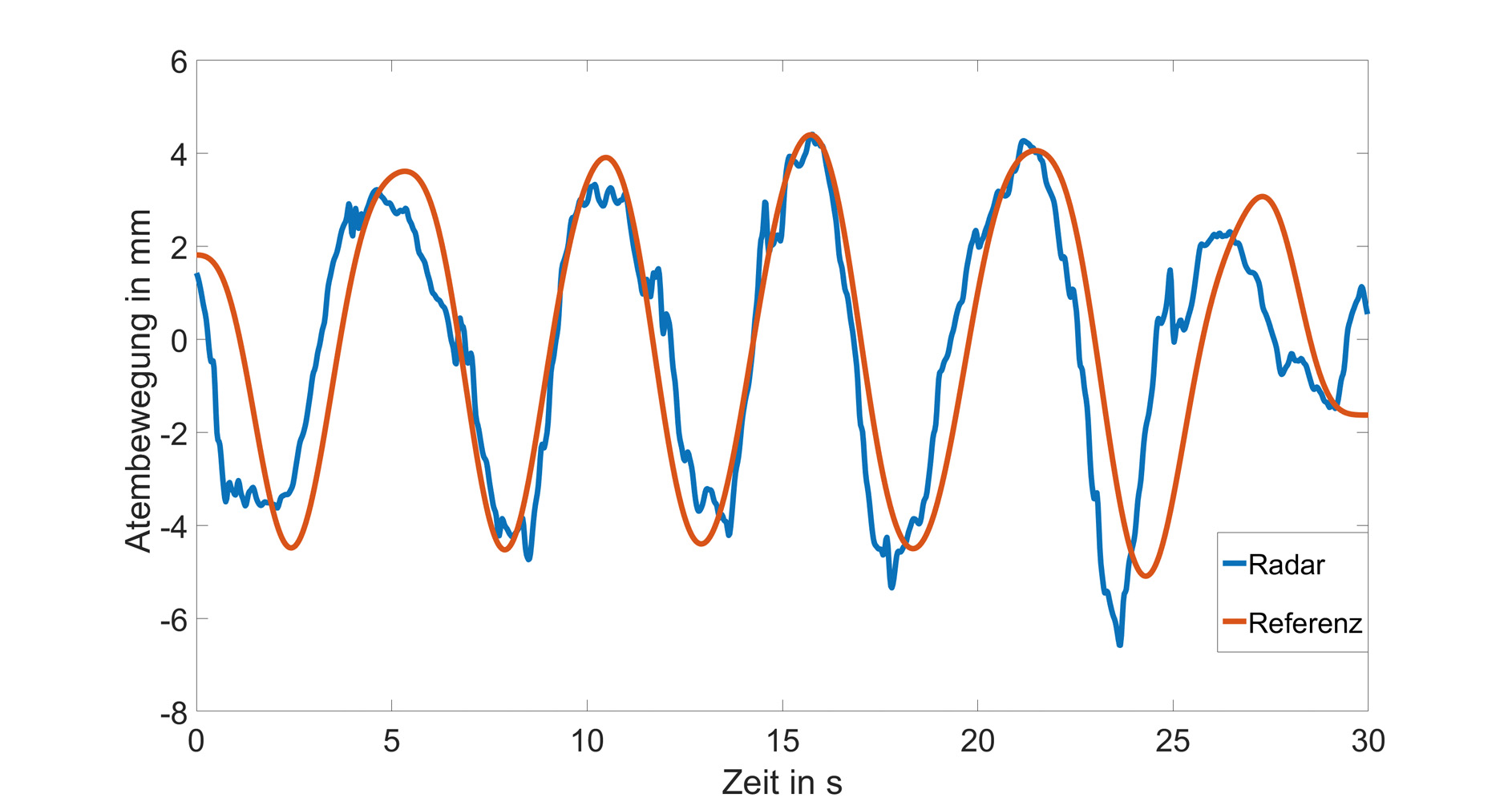

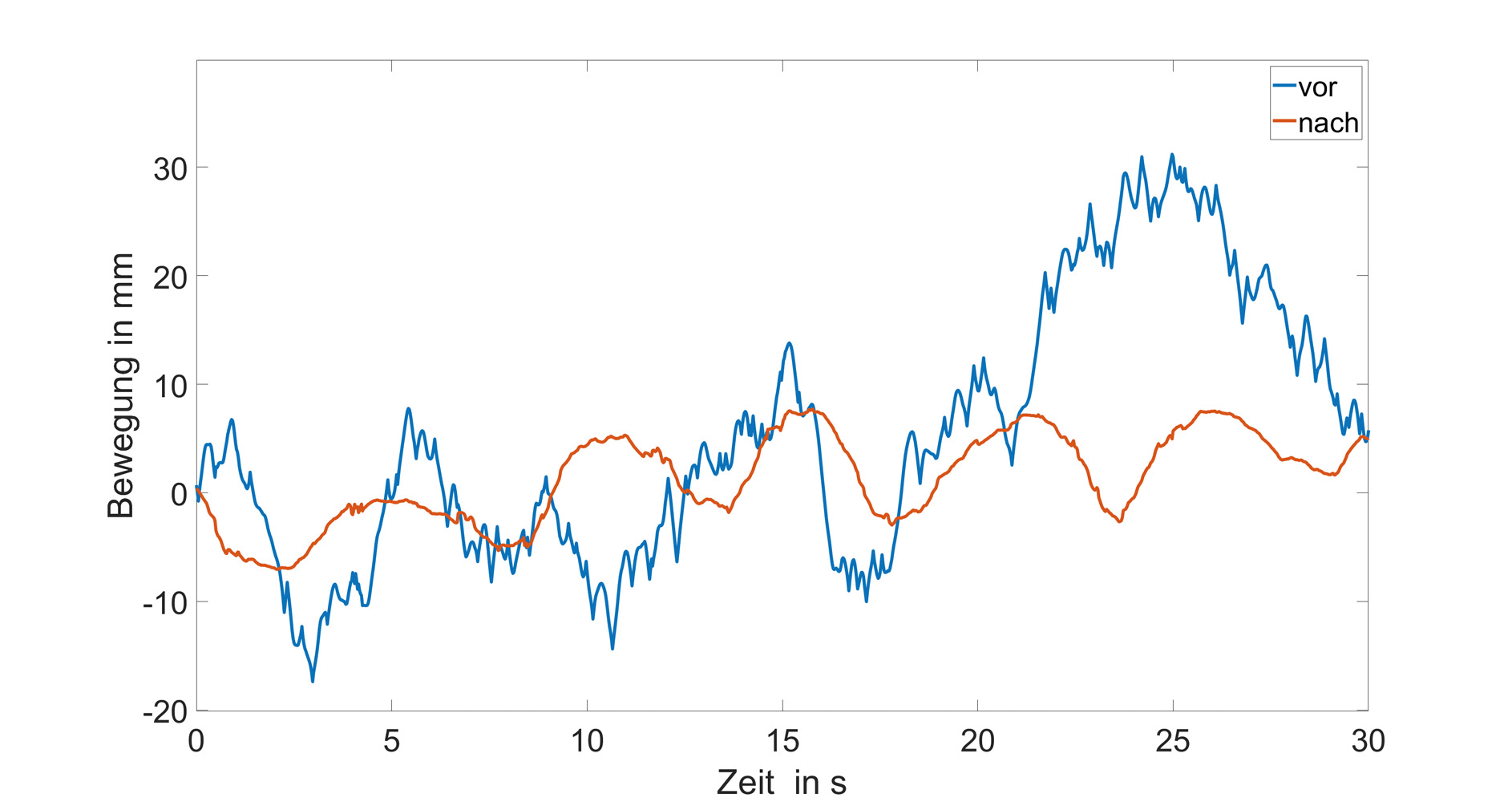

While the Austrian researchers analyzed and mapped the disaster area from above with a LIDAR system, the German team worked on a smaller drone equipped with radar and LIDAR that could fly into the collapsed building. This drone maps the interior and searches for injured individuals. The researchers at Fraunhofer FHR focused on detecting vital parameters. Analyzing heartbeat and respiratory rate via radar is state-of-the-art, but has so far always been done using stationary radar systems. This method analyzes the frequency at which a person‘s chest rises and falls with breathing and heartbeat. The researchers have now managed, for the first time, to record vital parameters from a moving radar system. This is no easy task: within one to two seconds, the drone moves about 20 centimeters, whereas the breathing movement is within the range of one centimeter—even when the drone hovers in place, its movement is greater than the one it needs to detect.

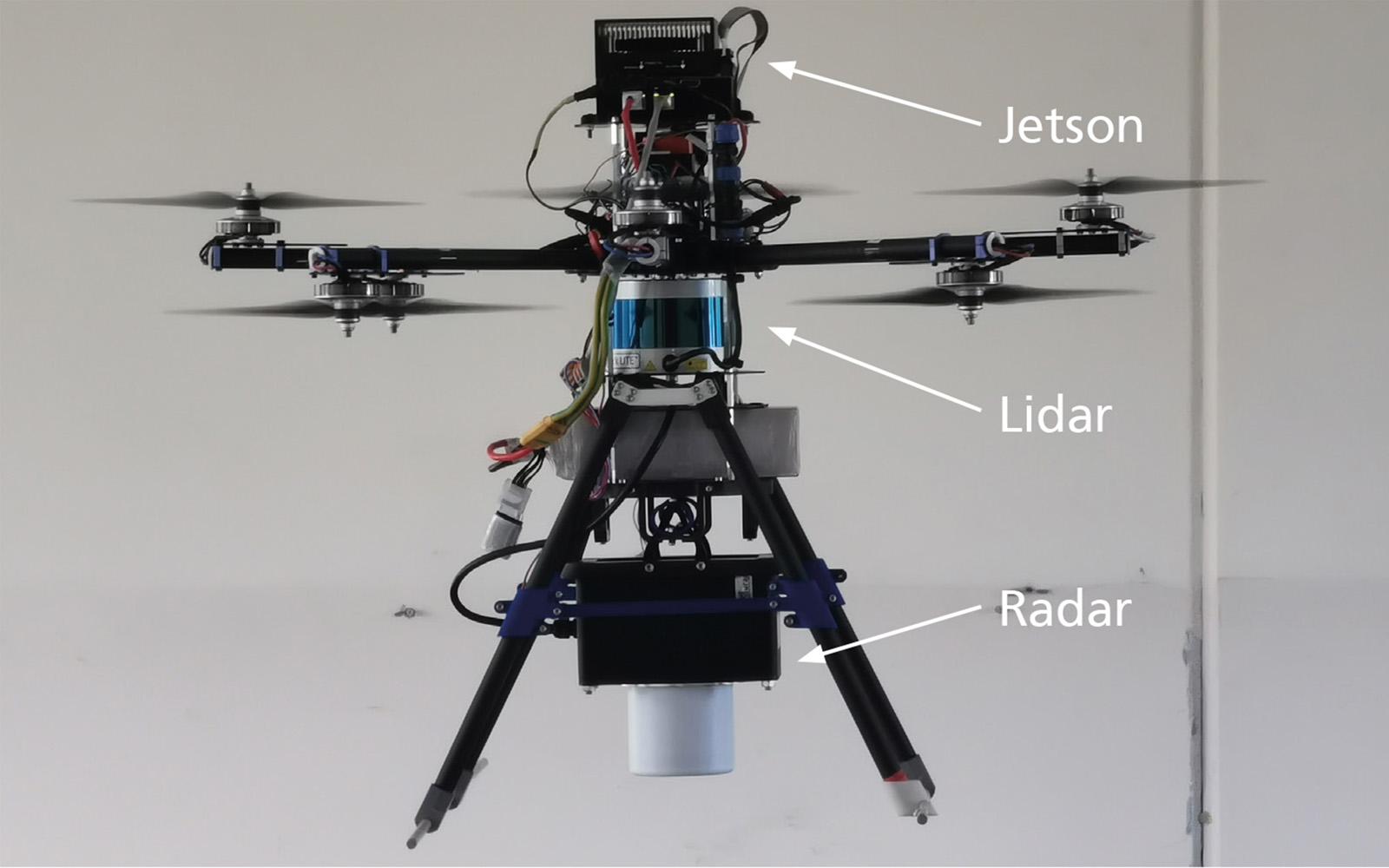

So how can the vital parameters still be resolved? The core idea: in the building, the rotating radar mostly sees objects that do not move, such as walls. However, due to the drone‘s own movement, it appears to the radar as if the walls are moving toward or away from it. The researchers use these stationary objects to analyze the drone‘s movement and subtract this movement from the overall radar data. The remaining targets are then evaluated: do they contain vital parameters? Is the frequency of a person‘s heartbeat or breathing recognizable within them? To perform such analyses in real-time, the drone is equipped not only with radar sensors—provided by the project partner Indurad—and LIDAR systems, but also with a small Jetson computer that processes the captured signals. The drone transmits its position, a map of the surroundings, the location of the person, and movement information, from which the vital parameters can be derived, to the rescue teams outside.

First Functional Tests Successfully Completed

A flying demonstrator has been developed and has repeatedly measured vital parameters from a moving drone: during a measurement campaign in Austria in 2022, in Mosbach in late June 2023, and at the project‘s final presentation in Austria in July 2023. The demonstrator created a map of the building, located a person within it, detected their vital parameters, and displayed the person‘s position on the map. However, further research is needed to bring the system to product maturity, which is expected to take about three to five more years. Future projects may focus on improving the system‘s robustness.